International Private Certifications Body for Entrepreneurs, Managers & CEOs Worldwide!

As you prepare to sell your business, you've taken a number of steps:

Now, how do you boil all of this down into an asking price for your business?

In order to ensure that you get the best price for your business, it is wise to hire an expert business appraiser. The appraisal process can be very complex and time-consuming. It takes quite a lot of experience to do well.

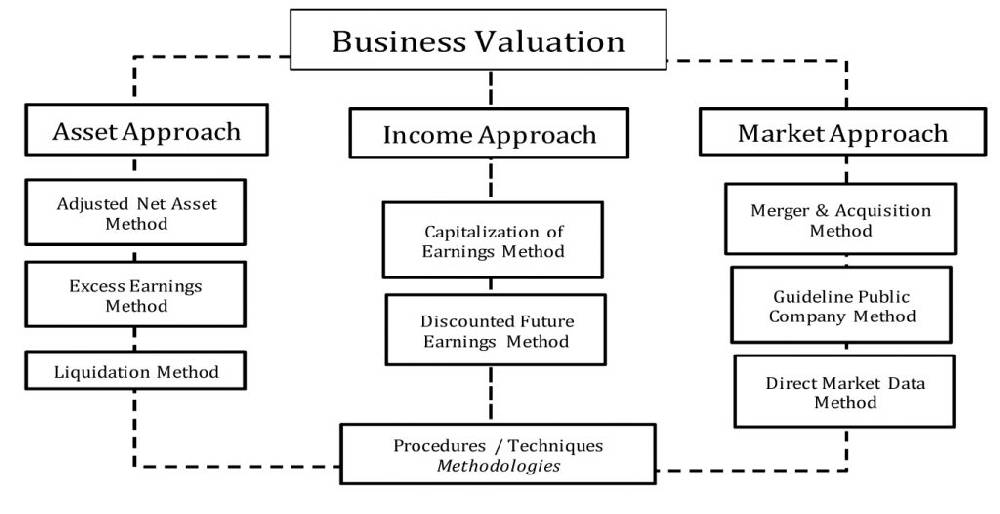

There are a number of valuation methods that business appraisers have at their disposal, and even choosing the correct method (or more likely, the correct combination of methods) to use in a given situation is more of an art than a science. The following discusses the major approaches commonly used to put a price tag on small businesses. Our objective here is simply to give you high-level insights into the process that your appraiser will be go through.

Business valuation methods fall into the following categories, depending upon their major focus:

Although no substitute for an appraisal and valuation by qualified professions, the Interactive Business Valuation Calculator can provide you with a rough idea of the value of your business.

At a minimum, your company should be valued at the sum of the value of its easily salable parts. Two commonly used business valuation methods look primarily at the value of your hard assets.

Warning: If goodwill or other intangibles are a significant component of your business, relying solely on a salable parts method could could result in a serious undervaluation of the goodwill component of your business.

Book value. Book value is the number shown as "owner's equity" on your balance sheet. Book value is not a very useful number, since the balance sheet reflects historical costs and depreciation of assets rather than their current market value. However, if you adjust the book value in the process of recasting your financials, the current adjusted book value can be used as a "bare minimum" price for your business.

Liquidation value. Liquidation value is the amount that would be left over if you had to sell your business quickly, without taking the time to get the full market value, and then used the proceeds to pay off all debts. There's little point in going through all the trouble of negotiating a sale of your business if you end up selling for liquidation value — it would be easier to simply go out of business, and save yourself the time, broker's commission, attorney's fees, and other costs involved in selling a going concern. Thus, liquidation value is not even considered a valid floor for the price of your business (and you can use this argument in negotiations if you get an offer that approaches liquidation value.)

In contrast to the asset-based methods, historical earnings methods allow an appropriate value for the goodwill of your business over and above the market value of the assets, if that's justified by your earnings. Although savvy buyers will be more concerned about the future of your business than its past, predicting the future is difficult. The assumption here is that your past history provides a conservative indication of the amount, predictability, and growth trend of your earnings in the future.

Most small companies are valued using one or more of the following methods, all of which take into account the company's historical earning power:

The starting point for all these methods is the recast historical financials that show how the business would have looked without the owner's salary and perks over and above what a non-owner manager would be paid, non-operating or nonrecurring income/expenses, etc. A judgment call must be made as to whether you should look only at the last year's statements, or at some combination of statement results from the last three to five years (the most common combinations are a simple average, a weighted average that values the most recent years more heavily, or a trend line that factors in the percentage and direction of growth each year).

Debt-paying ability. This is probably the method most commonly used by small business purchasers, because few buyers are able to purchase a business without taking out a loan. Consequently, they want to be sure that the business will generate enough cash to pay the loan off within a short time, usually four to five years.

To entice a buyer, therefore, the price must be set at a point that makes this short-term repayment possible. To determine the company's debt-paying ability, you'd need to start with the historical free cash flow. Free cash flow is usually defined as the company's net after-tax earnings (with a reasonable owner's salary figured in) minus capital improvements and working capital increases, but with depreciation added back in. Interest on any existing loans is usually ignored, so that you start with a picture of the company as if it were debt-free.

Next, multiply the annual free cash flow by the number of years the acquisition loan will run. From this amount, subtract the down payment. The remainder is the amount available to make interest and principal payments on the loan, and to provide the new owner with some return on investment.

Example

Your free cash flow was $80,000 a year and it's reasonable to expect the loan to be repaid in four years,

4 x $80,000 = $320,000.

If the down payment were $80,000, then no more than $240,000 (or $60,000 per year) would be available to make interest and principal payments on the loan, and to provide the owner with some return on the investment ($320,000 - $80,000 = $240,000. $240,000/4 = $60,000).

If the owner expected a 20 percent return on this $80,000 down payment, that would translate to $16,000 per year, further reducing the amount available to make debt payments to $44,000 ($60,000 - $16,000 = $44,000).

An annual payment of $44,000 could support a four-year loan of approximately $139,474.08 at 10 percent interest, or $145,733.58 at 8 percent interest. Add the loan amounts to the down payment, and you arrive at a total purchase price of $210,685 at 10 percent, or $225,000 at 8 percent. If the lender is willing to finance the deal for a longer term or a lower rate, a higher price would be possible.

Capitalization of earnings or cash flow. This is another commonly used method. Basically, it involves first determining a figure that represents the historical annual earnings of the company. Generally this is EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) but sometimes EBITD (earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation) is used. Some buyers prefer to use free cash flow, as discussed above.

The chosen figure is divided by a "capitalization rate" that represents the return the buyer requires on the investment in light of the market rate for other investments of comparable risk. For example, if the EBIT was $100,000 and the buyer required a return of 25 percent, the capitalization of earnings method would yield a price of $100,000/.25 or $400,000.

Gross income multipliers/capitalization of gross income. Where expenses in a particular industry are highly predictable, or where the buyer intends to cut expenses drastically after the sale (for example, where the buyer is already in a similar business and can centralize administrative functions), it may be reasonable to value the business based on some multiple of gross revenues.

For example, some service businesses can be valued at four times their gross monthly income. A variation on this would be to divide the gross income figure by a capitalization rate, as with the capitalization of earnings method discussed above.

The problem with either of these methods is that they ignore the fact that two businesses in the same industry with similar revenues can have greatly different profitability margins, depending on their expenses.

Read more:https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/best-business-valuation-formula-for-your-business