International Private Certifications Body for Entrepreneurs, Managers & CEOs Worldwide!

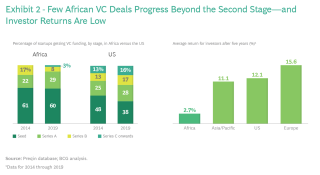

Africa’s record of sustaining and scaling up startups, unfortunately, is another story. The entire continent has only three “unicorns”—privately held tech companies valued at more than $1 billion—the most recent being Nigerian fintech Flutterwave. By contrast, there are more than 50 unicorns in the EU, 100 in China, and 200 in the US. In fact, by our count there are fewer than 20 African “zebras” (valued at least $200 million).1 African startups rarely survive beyond the Series B funding stage. As a result, returns on venture capital investments are weak—less than 3% on average across the region over five years, compared with around 11% in Asia-Pacific and nearly 16% in Europe. (See Exhibit 2.)

A number of structural barriers make Africa challenging for tech entrepreneurs and investors. They include a fragmented market of 54 countries, low consumer purchasing power, complex and inconsistent regulations, inadequate data communications infrastructure, and scarce capital and digital talent.

But even if startups navigate those obstacles, many run into the hard realities of Africa’s competitive playing field. Key sectors, especially business-to-consumer ones such as financial services, retail, and energy, are controlled by large business groups or state monopolies that are regarded as national champions. Although such enterprises are supposed to use their privileged position to advance the national interest, they often use their market power and connections to stack the odds against new entrants with disruptive business models.

Africa’s inhospitable startup environment not only stunts job creation and economic development. It also threatens the competitiveness of Africa’s national champions themselves by depriving them of crucial sources of innovative technologies, products, and business models. Over time, Africa’s biggest companies will grow increasingly dependent on the world’s leading technology players in their segments, and profit margins will shrink.

Nevertheless, Africa remains enormously fertile ground for tech entrepreneurs. Its population is young and growing, internet penetration is rising fast, and there are tremendous opportunities for digital innovators to use artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies to improve access to education, health care, financial services, and energy. To realize this potential, however, startups will need to develop new strategies, and Africa’s national champions, investors, and governments will need to work together to tackle the substantial obstacles they face.

Large established enterprises already have the means and assets needed to overcome the region’s structural challenges. They have access to capital, the expertise needed to navigate complex regulatory environments, and often a presence in multiple markets. Therefore, rather than trying to compete head-on for consumers, African tech innovators will have a greater chance of success if they collaborate with those larger entities by providing innovative business-to-business solutions.

But African national champions must be willing to open up and engage with innovative new businesses as true partners. The partnership model is already well-established in financial technology. Of the African fintechs we examined that have achieved zebra valuations, including Ghana’s JUMO, Egypt’s Fawry, and Nigeria’s Interswitch, three-quarters are allied with larger corporations, such as banks and telecom operators.

Such collaborations can take several forms. Incumbents can nurture startups through direct investments or partnerships with external labs and incubators. Indonesia’s Lippo Group, for example, provided initial financial backing to OVO, a leading digital payment service. In its early stages, OVO benefited from the conglomerate’s huge ecosystem, which spans hypermarkets, telcos, e-commerce marketplaces, content streaming, and banks serving small and midsize enterprises. For its part, Lippo got valuable help from OVO to bring merchants onto its platforms and provide incentives for consumers. To succeed with such an inorganic innovation model, the large enterprise must have a clear vision, empower dedicated teams to collaborate with startups—and play fair with its partners.

Another path for incumbents is to form strategic alliances with startups. Many leading African corporations are seeking to enrich their ecosystems with partners that bring new digital technologies or innovative business models to the table. Collaborations can take the form of revenue-sharing partnerships, joint ventures, or technological alliances. And they can include several companies.

The Ghana-based mobile financial services platform JUMO illustrates how such win-win collaborations can enable a startup to grow into a zebra. Several major Africa telecom operators share behavioral and mobile-wallet data of willing customers with JUMO, which has a proprietary credit-scoring algorithm. JUMO then provides credit scores to its financial institution partners, which include Ecobank and Letshego, when they review consumer loan applications. This alliance has enabled banks to reach big, untapped markets of consumers. Telcos are earning new revenue from data sharing, and JUMO is gaining access to a far wider customer base for micro loans.

Another route is for large enterprises to launch startups themselves. This approach enables companies to overcome internal processes and cultures that inhibit innovation. Established companies can foster homegrown startups through their own incubators or accelerators. This strategy requires strong commitment from top leadership, minimal administrative interference, and the ability to attract and galvanize talent. One of the most successful new businesses launched by an African conglomerate is Kenz’up, incubated by Morocco’s Akwa Group, which is active in oil and gas distribution and retail. Kenz’up aims to become the country’s leading open loyalty platform. By leveraging Akwa’s network of gas stations, Kenz’up reached more than 1 million users in less than six months and has become one of Morocco’s most popular apps.

Governments and investors have important roles to play in improving Africa’s startup ecosystem and making it easier for new companies to scale up through alliances with large companies. Governments should offer financial incentives—and issue mandates—for national champions to collaborate with and nurture nascent businesses. Investors should strive to create linkages between the African corporate and startup worlds.

In an attempt to replicate the high-tech clusters of more advanced economies in Asia and the West, several African nations are developing “innovation hubs” that they hope will amplify partnerships between large companies and startups and draw talent and foreign investment. Rwanda and the African Development Bank have invested $400 million so far in the 70-hectare Kigali Innovation City, for example. Morocco’s OCP Group, a state-owned fertilizer company, is powering an equally ambitious innovation zone within the campus of Mohamed VI Polytechnique University in Ben Guerir that aims to develop the nation’s first ecosystem for collaborations involving startups, academia, and established companies. Nations such as Nigeria, South Africa, Rwanda, and Tunisia have offered tax incentives and cash grants for investing in sectors such as information and communications technology.

Some African governments are also acting to harmonize the region’s governance systems for investors. The eight member nations of the West African Economic and Monetary Union is implementing a comprehensive legal and regulatory framework for private equity and venture capital funds in partnership with the World Bank.

Much more needs to be done across the region. Governments should use their leverage over national champions to get them to invest more in innovation and to open up their ecosystems to promising new ventures—as OCP Group is doing in Morocco. Governments must also do more to improve the regulatory and investment environment for startups. Despite the rapid growth—the number of startups that secured funding soared from just 55 in 2015 to 359 in 2020, according to Partech—venture capital funding equals less than 0.3% of GDP even in Africa’s largest economies, compared with around 1% to 2.5% in UK, US, China, and Israel.

Governments can also help mitigate the risks arising from collaborations between startups and powerful incumbents by enacting clear and strong protections of intellectual property and data. Moreover, governments can bring trade laws in line with new business models and clarify current ambiguity over how they allocate responsibilities and liability between startups and established corporations.

Venture capital funds can widen the pool of potential zebras by making corporate partnerships the heart of their value proposition. Rather than adopting a “spray and pray” approach to investing, venture capitalists should provide hands-on support to new businesses by introducing them to potential partners, helping frame win-win collaboration models, and sourcing talent through late funding stages. Such support could help close the seed-funding gap between Africa and more advanced economies.

Making Africa a more fertile environment for dynamic technology startups should become an urgent priority of both the public and private sectors. Doing so will not only generate more zebras and unicorns that can create wealth for entrepreneurs and investors. It also will unleash a wave of innovation that will create jobs, economic opportunities, and greater access to health care, finance, and education across the continent.